From 1936 to 1939 Rothko participated in art projects supported by the Works Progress Administration, a government agency founded in the aftermath of the Great Depression to help provide jobs to the unemployed. In addition, he banded together with like-minded artists to mount exhibitions of their work and combat the stranglehold of regionalism in American art. It was also at this time that Rothko had his first exposure to Surrealism. He attended several exhibitions of Surrealist work, including an important 1936 survey at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and met Surrealist emigres, such as Andre Breton, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Matta, who had fled to New York during World War II.

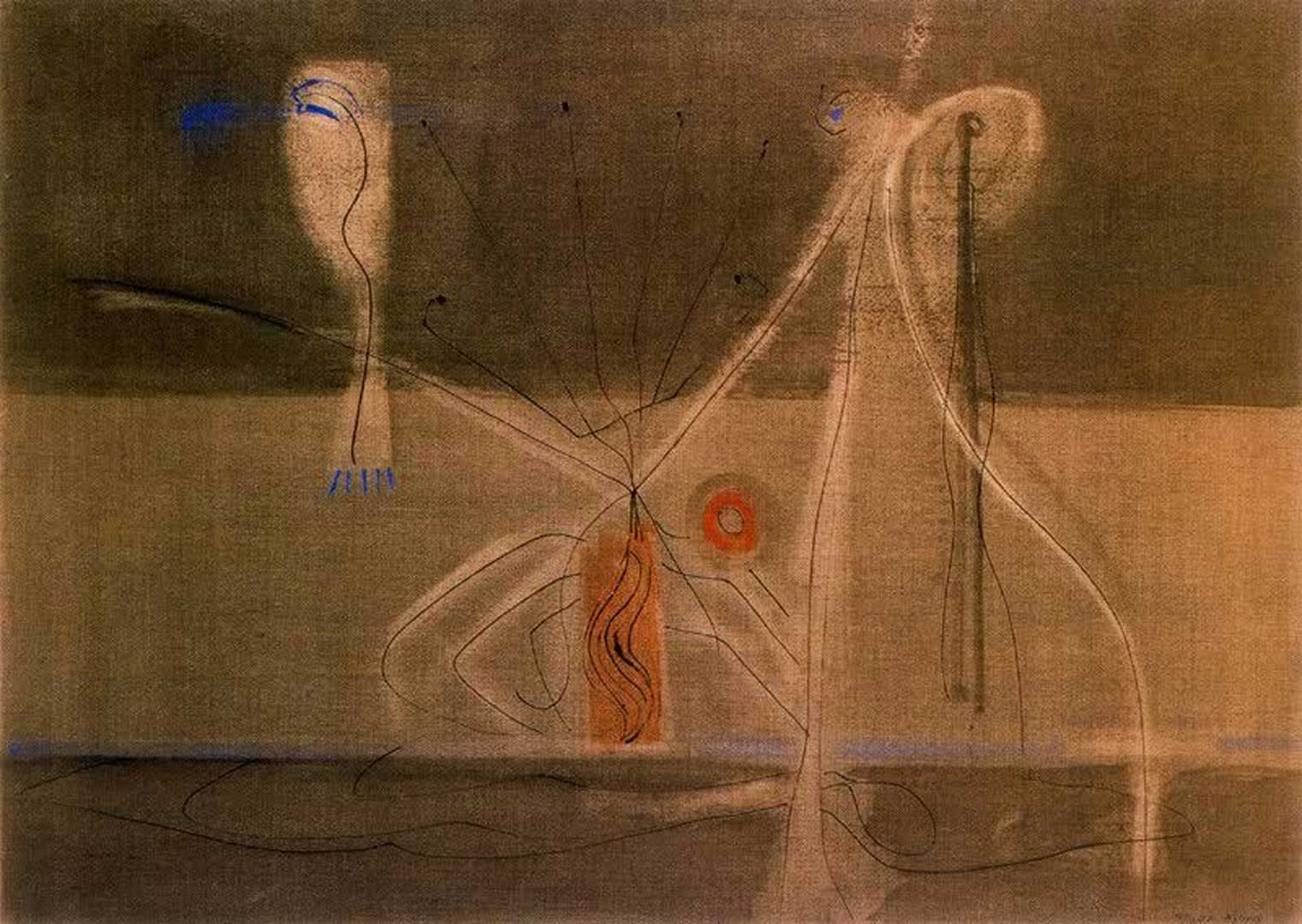

In the late 1930s Rothko and Gottlieb adapted Avery's method of using different registers to structure the composition in a series of paintings that incorporated mythic symbols and archetypal figures drawn from Surrealism, the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung's theories of the collective unconscious, and primitive and archaic art. Rothko also found inspiration in literary and philosophical texts ranging from ancient Greek tragedy to Friedrich Nietzsche's Die Geburt der Tragodie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, 1872). Tentacles of Memory, exemplifies this period in Rothko's development, and echoes Rothko's 1945 statement:

"...Our paintings, like all myths, combine shreds of reality with what is considered unreal and insist upon the validity of the merger."

In the summer of 1946, both the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art mounted exhibits of Rothko's surrealistic seascapes, and the Rothkos went west for a visit. The museum was considering the purchase of a watercolor, Tentacles of Memory, for $150. His large oil Slow Swirl by the Edge of the Sea had a "beautiful hanging in the rotunda of the museum - I cannot describe the adulation I have received from the artists in San Francisco." That summer and the next, when he taught at the California School of Fine Arts, he became fascinated with the work of Clyfford Still, who was venturing into new and beautiful abstractions, as Rothko wrote, "Still's show has left breathless both my students and everyone else I have met."